Project aims

The aim of the Hyrban project is to develop a highly energy-efficient vehicle that is built to last and cheap to maintain.

Design approach

Our approach is based on whole system design. This means optimizing not just the parts, but the whole system.

We aim to use current state-of-the-art technology, which does not depend on great leaps forward in the laboratory.

Starting point

The starting point will be the vehicle designed and built by Riversimple, a network electric hydrogen fuel cell powered urban vehicle - see the Riversimple website for more information. Riversimple has licensed its designs for the urban car to 40 Fires for no charge. They have developed the technology demonstrator. Here are some images from the workshop.

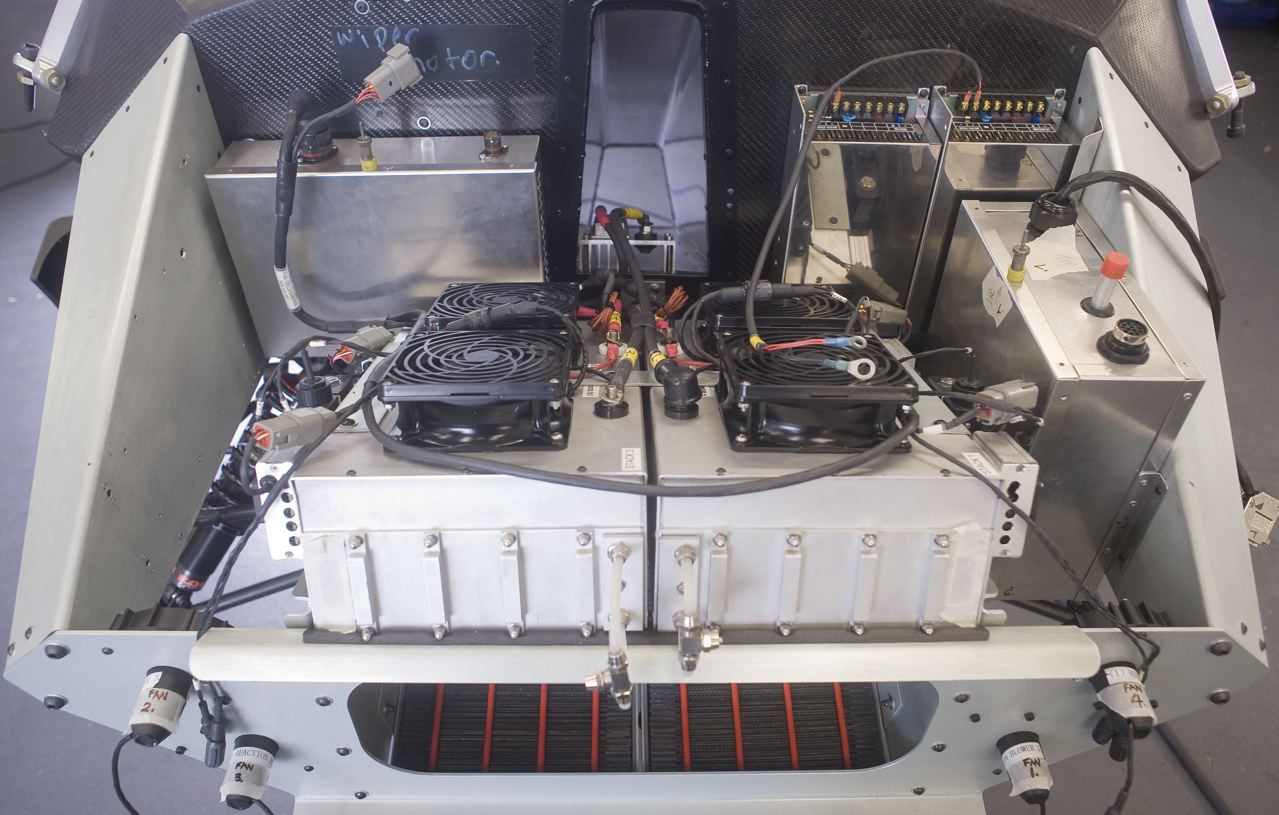

Under the bonnet

Under the bonnet

A picture from the workshop of the bodyshell

A picture from the workshop of the bodyshell

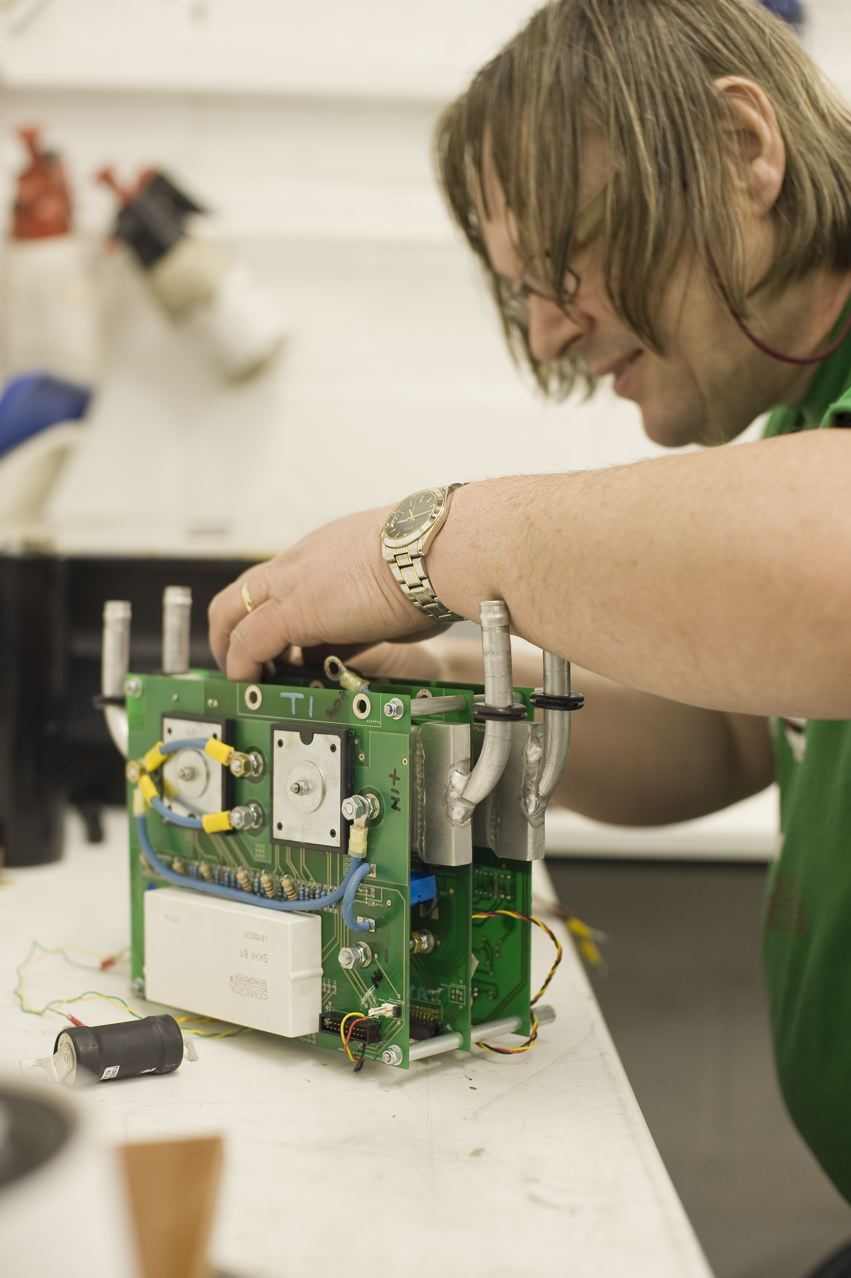

Working on the electronics

Working on the electronics

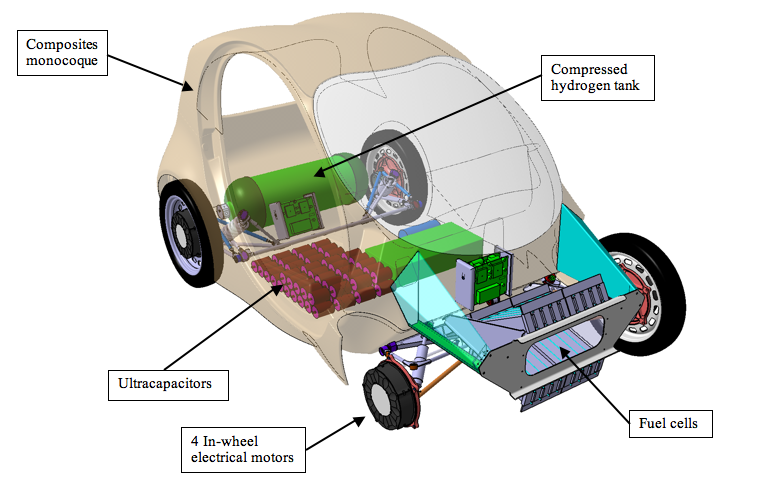

Hyrban layout

Hyrban layout

Detailed designs available

[Hyrban rear suspension]

[Hyrban front suspension]

Please follow this link for access to CAD models: Hyrban CAD models

Specification

Here is the draft specification of the vehicle:

| Installed range: | 220+ miles (352 km) |

| Top speed: | 50 mph (80 kmh) |

| Number of passengers: | 2 |

| Carbon emissions, well to wheel | < 31g CO2/km |

| Energy Consumption equivalent: | 300 mpg |

How the car works

The car is powered by a fuel cell, a hydrogen-driven electricity supply. The fuel cell converts hydrogen to electricity without any moving parts, and the only byproduct is pure water. Thus, a ”reversed electrolysis process” has been performed in the fuel cell, which can therefore be treated like a battery; it will never have to be recharged but will deliver electricity as long as there are added hydrogen and oxygen (or simply air will be sufficient). Click here if you are interested in Hydrogen Safety..

The two principles that really are new in the Hyrban (originally conceived by Amory Lovins and the Rocky Mountain Institute) are:

-

decoupling acceleration and cruise demands and

-

mass decompounding

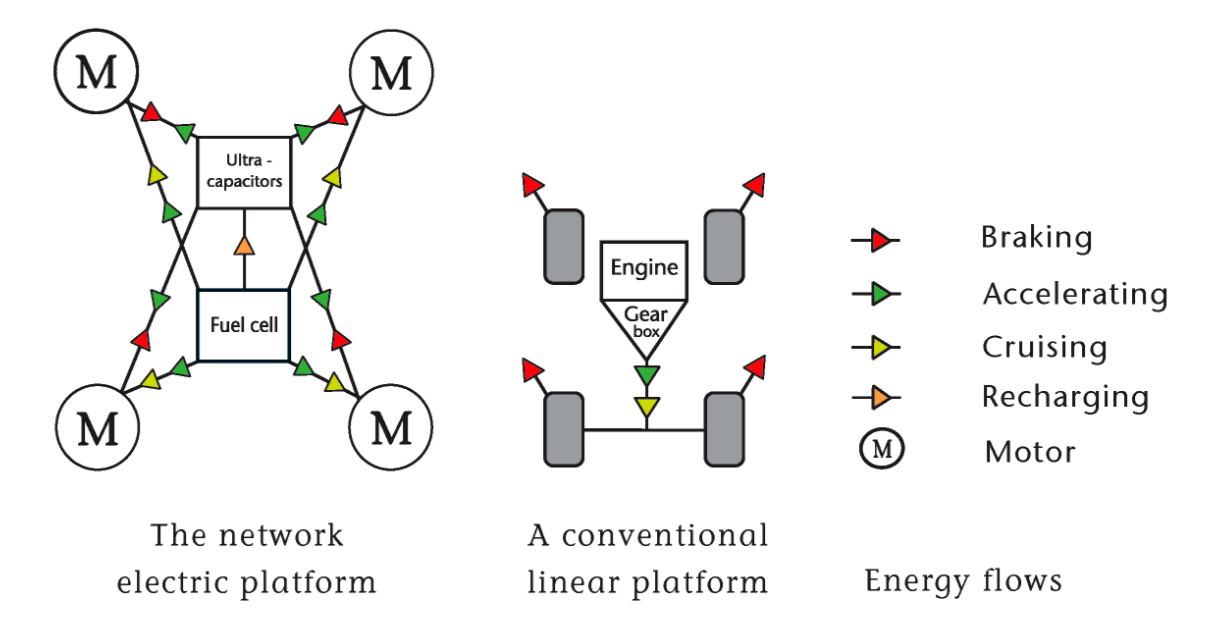

Decoupling acceleration and cruise means that the fuel cell needs only to be large enough to meet the maximum steady demand when cruising for which the vehicle is designed, which is usually only about 20% of the maximum power required when accelerating.

In a conventional car, acceleration also has to be provided by the engine; but as a car is only accelerating for about 5% of the time, and the power needed then is five times what it is when cruising, it means that for 95% of the time the car is carrying around an engine and transmission that is five times larger than necessary.

In the Riversimple network electric vehicle, almost all braking is done by the electric motors, capturing the energy of the car in motion, rather than using conventional brakes that just waste the energy as heat. This energy is stored in a bank of ultracapacitors which thus provide 75% of the power required for acceleration. This allows us to have a fuel cell a fifth the power than would be required in a conventional car.

Mass decompounding is an emergent property of whole system design – designing the car as a whole system rather than attempting to squeeze a fuel cell into a car architecture that is designed for a combustion engine. The reduced size of the fuel cell and elimination of a gearbox and driveshafts, results in a weight reduction. This leads directly to a lighter chassis, as this is designed to hold on to the heavy bits (engine and gearbox) in accidents. This in turn means less power, which means lighter components, means lighter chassis, means less power and so on, and this effect is magnified by using lighter materials, composites, for the chassis as well. All these weight reductions make power assisted systems for brakes and steering redundant, which again leads to further mass decompounding and improvements in efficiency.

A diagram showing the flows of energy throughout the system

A diagram showing the flows of energy throughout the system

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License